Saying goodbye to the world’s first surf park – Arizona’s Big Surf

Welcome. Please be seated. We’re gathered here today not to mourn a loss but to celebrate a life well-lived – one of countless waves and good times. And, yes, there was that one time the Pope blessed our beloved wave pool.

And it was with a slew of sad emoji faces on our devices that we learned of the closure of Arizona’s Big Surf – the one, the only, the original and dare we say it – an inspiration for the tech that followed. And though not as refined as today’s similarly styled characters, the stoke was real.

What, if any, wave pool phoenix may rise from Big Surf’s ashes, we’ll have to wait and see. But with five pools already in planning stages in the state, who knows if there’s room for another?

It looks as if Big Surf was a Covid casualty, a long closure hastened its demise, and the rapidly aging tech didn’t help. No amount of software updates were going to help. Big Surf was unashamedly of an analog era, plus there’s no shortage of water parks in Arizona. While Big Surf suffered the ignominy of having some of its chattels sold off for pennies on the dollar, it’s the rich history of the place that vastly overshadows its ending. History runs deep with this one.

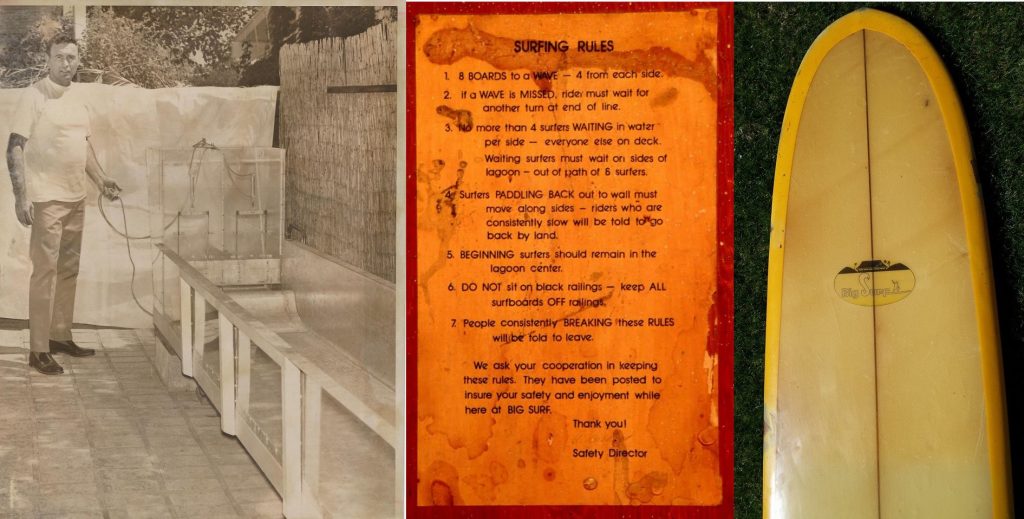

Phil Dexter was the original brains behind the operation. As a sailor in the U.S. Navy in World War Two, he became enamored with waves. In 1967 he then went on to design and build a test tank, 40 feet by 30 feet and holding 1000 gallons / 4500 liters of water, that produced waves in a repurposed old pool hall. The windows were papered over, partially for secrecy, as well as self-preservation. The neighborhood he was in was ground zero for the civil rights riots in Phoenix. Protests, which often turned violent, were sweeping across America that hot, sticky summer.

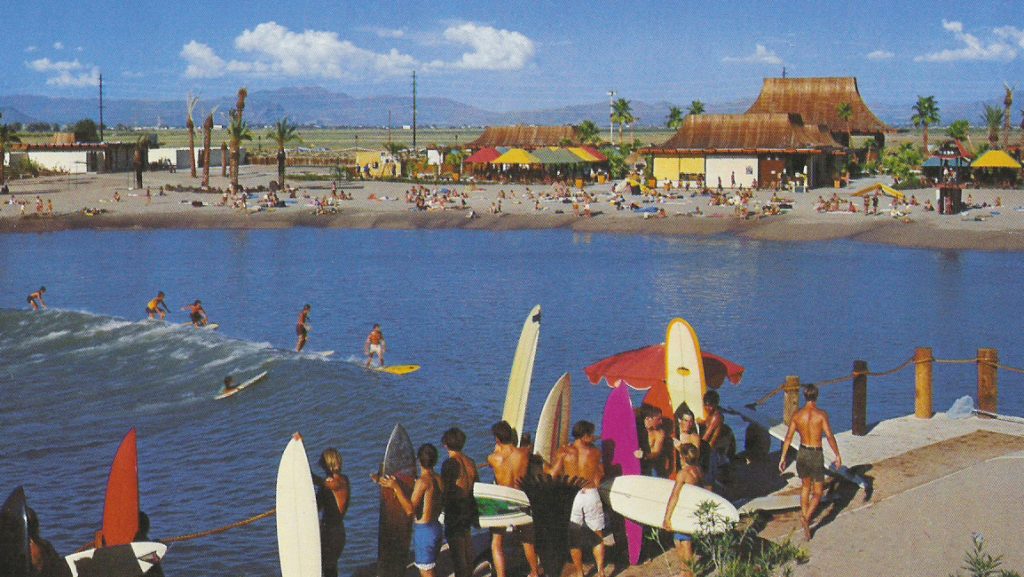

Fast forward to 1969, and nine miles up the road, the world’s first wave pool opened. It was the first time in history where waves would wait for every man and woman willing to pay an admission fee. Big Surf’s lagoon spanned 2 1/2 acres and 50,000 gallons of water were displaced each time to create rideable waves. A baffle regulated the flow of water and a submerged gate released it into the lagoon, creating unbridled stoke for surfers.

Originally financed in ‘67 by hair company Clairol, as a tie-in to promote their real gone ‘Surfie’ look – it turned out to be a bust for them, but a boon for everyone in Arizona. By the time the pool was up and running, 2 years later, surfers (and the poor deluded wannabe-surfer dudes and dudettes wanting to craft their locks as such) had moved on from bushy blond hairdos to the long, unkempt hippie hair. Clairol also sponsored and supplied wax for the boards – a grand gesture until the promo wax began melting in the Arizona summer heat.

This venture wasn’t without other hiccups either. When Big Surf began testing, the force of the waves twice tore up the bottom (which also occurred with the failed Ron Jon wave pool in 2008 leading to them halting the venture) of the lagoon. Meaning that 2.8 million gallons of water had to be drained each time so repairs could be made.

23,000 tons of gravel was imported from an Arizona dam for the Big Surf beach, and while the owners were assured it had been cleaned, it turned out not to be as the entire pool started to resemble the “Lower Ganges Canal on washday” as Sports Illustrated (November 10, 1969) wrote at the time. After countless days of filtering and re-filtering the pool, the mud finally cleaned.

With the surf, beach, and palm trees, it was idyllic. Impressed by the realism of Big Surf, reporter Robert Allison of the Phoenix Gazette wrote in 1969: “The only thing it needs to duplicate a penned-up portion of ocean beach is a few old beer cans and some tar on the sand.”

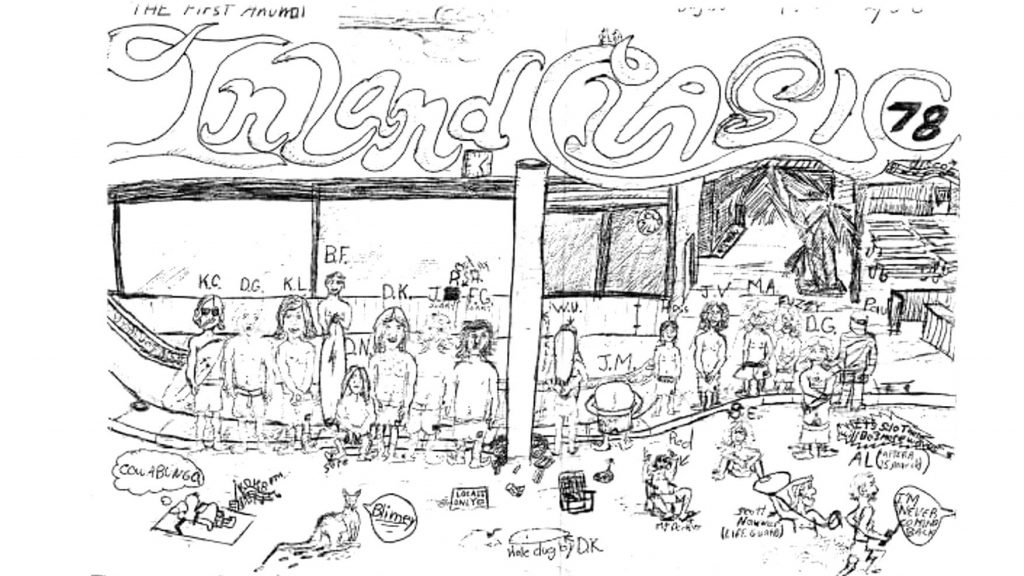

More than just a touchstone to a surf and beach culture many miles away, it spawned its scene complete with local rippers, a plentiful and never-ending supply of beginners, beach dwellers, groms gripped with surf fever, and hosted an intricate surf-focussed social fabric as full and as vibrant as any beach culture, anywhere in the world.

John Malpede who now lives in California, but spent his youth at Big Surf, said there were distinct crews and that the bonds formed at that time still remain today.

“I learned to surf back at Big Surf around 1975, and I think I would have been considered part of the Generation 2 crew,” said John. “From my perspective, Gen 2 surfed at Big Surf from the Mid ’70s to the early ‘80s. I consider the Gen 1 crew as those crew who first surfed it in 1969. It was our passion for surfing that brought us together to form a brotherly bond that still exists today. Most of the core Gen 2 crew still keep in touch and frequently go on surf trips today.”

The Baffle

John added that the wave pool required special knowledge unique to the spot. The baffle was the underwater structure right next to the back wall that helped form the wave. It was the structure where water would get released from the tank, hit the baffle, which then would create the wave that rolled on out to the lagoon. It was the most powerful part of the wave.

To get the most out of each wave, surfers would paddle out to the back wall and wait on the baffle for their next wave. It was during the wait for the wave that was the biggest challenge, because it was all timing for a successful no paddle takeoff or getting pummelled to the bottom of the lagoon and dragged across the cement for what seemed like an eternity.

“There were many times a surfer would be standing on the baffle when the wave would prematurely launch and they would get sucked down to the abyss below,” said John. “It was a pretty scary experience, but what made it worth it was coming up hearing the hoots and howls of your buddies that saw your misfortune while waiting for their next wave.”

Duct Tape

Wave pools were hard on boards, even back then when your average single fin had boat-quality glass jobs.

“Due to the cement bottom, decorative rocks, and no leash mentality, our boards were always getting dinged,” said John. “As a quick fix, we would slap on some duck tape in between surf sessions, so that we wouldn’t miss out on the next session.”

John said the duct tape was supposed to be temporary, but back then surfboard resin was hard to find, so the duct tape soon became the preferred solution for ding repair. He added that it was a badge of honor if your board was covered in duct tape, and how clean you could apply it.

Pecking Order

John said that back then the rules limited the number of surfers to a wave to eight. Each wave would have a right and left where two surfers on each side would have a chance to get the best rides. The four surfers in the middle were relegated to a white water ride straight to the beach. Naturally, this created a desire to obtain an outside position, so that you would get the opportunity for the best possible ride.

Since everyone wanted to get the best possible ride a pecking order soon came to fruition.

The pecking order went like this: The older, more intimidating surfers muscled their way to get the outside position. It was then followed by skill from best to worst to fill in the rest of the spots.

“So, there was always excitement when a session started and you realized that you were going to get an outside position on the wave.”

Another Gen 2 surfer, going by the non de plume of Krayfish, said that in the early years, surfers had three attempts to catch a wave.

“So there were guys taking advantage of that to improve their take-off skills,” said Krayfish. “This did not sit well with people waiting, so there were numerous conflicts as a result. Eventually, the rules changed to a one-shot chance. I would also add some of the locals would at times force everyone else to the far side of the take-off lineup. People from elsewhere quickly learned that Big Surf had its own set of locals ruling the roost, and who could be merciless against an improper attitude. Just like many other surf spots.”

Barry Finnerty, who also grew up with Big Surf as the nucleus of his grommet life said Big Surf was affectionately referred to as “the flush” by us locals.

“Big Surf was more than just an amusement park or novelty, it was our life,” said Barry. “We were locals and we went every day from March to September, the normal months of operation. The cost was fairly inexpensive, I could get discounted daily tickets from my father’s employer for $2.50. Big Surf offered in and out privileges with a re-entry stamp. We would get to know some of the staff and lifeguards and sometimes they would let us in for free. On occasion, when someone would exit, we’d lick the back of our hands and try and transfer the stamp to gain free entry.”

Barry said the surf sessions were one-hour intervals and were two times a day midweek and three times on weekends.

“You would wait in line, like a Disneyland ride, on either side of the lagoon by the back wall and traverse down a set of stairs,” added Barry. “Four surfers were allowed from each side per wave. On any given day there might be 20-30 surfers, so you would be lucky to get 3-to-5 waves each session.”

The custom-made surf environment was not without its challenges. The average daily temperature was 105 degrees during the summer. Barry said the large, coarse grain sand got extremely hot but as the summer days wore on, the soles his feet would toughen up enough to walk on it.

“Naturally keeping wax on our boards was challenging. There was a snack bar with a large gazebo screen in the center of the park. We claimed this as our turf, our boards stored in the shade and we would sit on the wall surrounding the snack bar or on the beach right in front of it.”

He said there was as much of a surf culture present at Big Surf as in any Southern California beach town.

“I can’t express enough how impactful for me, the history, memories, and lifelong friendships that were developed there played a role in who I am today. We had coming-of-age experiences together and the typical pranks and shenanigans of young boys…groupies, summer romances, parties, etc.”

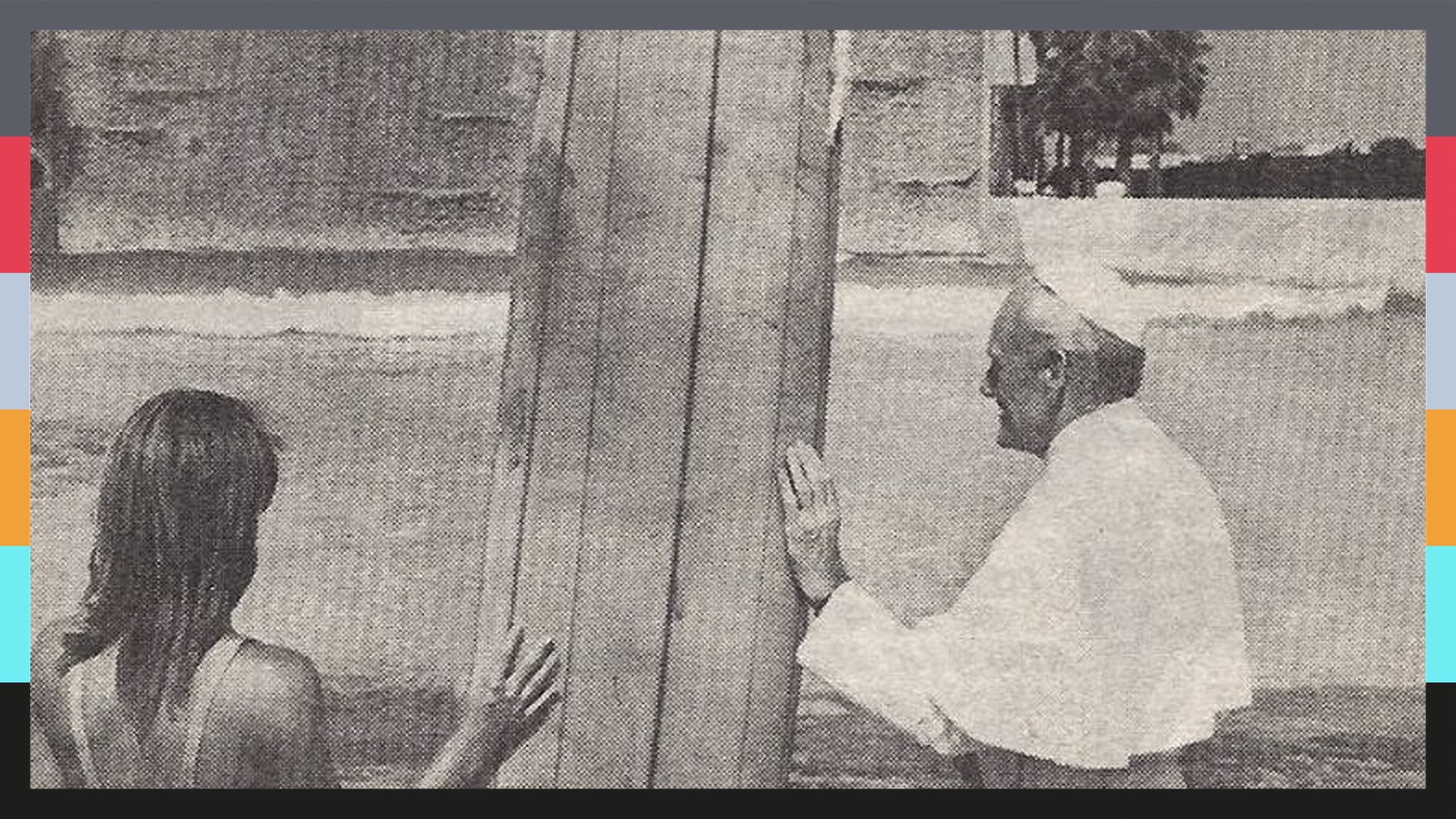

There were a couple of other notable occurrences that took place there. The only Pope to visit the state of Arizona was Pope John Paul II in September 1987. He held a mass at ASU for 78,000 plus attendees, and he also visited Big Surf.

Additionally, a television pilot was filmed there. American Girls starring Priscilla Barnes (Three’s Company). Many of the crew were paid extras to surf during this filming.

Big Surf was the first of its kind by a long shot. That it was operational for over 50 years is truly an amazing story. And years from now, when some of the modern era pools may close, it’s intriguing to think that similar tales of camaraderie, lifelong friendships – as well as shenanigans – are likely to be told.

Related Coverage