How Big Surf in Tempe cut the modern wave pool template

Big Surf in Arizona was way ahead of its time. The world is just now catching up some fifty years later. Go ahead and make fun of Rick Kane and the cult classic “The North Shore,” but as more wave pool projects emerge each month we’re finding that the surf park song remains the same. Through some digging and an old issue of Tempe Magazine, we discovered there was as much press and media around Big Surf Arizona as there is today around Kelly’s Wave.

In 1969/70 Big Surf magically mixed the same potent ingredients used for this modern world’s successful wave venues. The recipe reads something like this: take genius inventor smitten with the beach lifestyle and surfing, secure investors, build the damn thing, make a marketing push and create a flourishing surf scene.

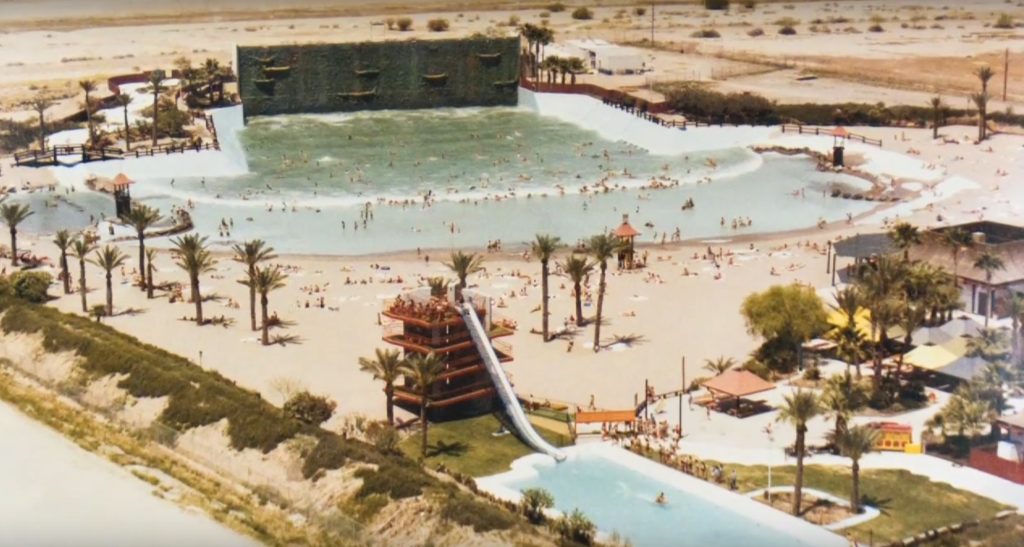

It worked for Big Surf. Desert kids ditched the river to spend summers in the surf. Dudes in cut-offs and femmes in crocheted bikinis flocked to the artificial Waikiki Beach in Tempe. Today, the barbecue-and-brew-set in Waco is not too far off the mark of this brand of summer fun – just replace pop-top cans of Coors with longnecks of Lone Star.

Genius inventorEach wave pool needs a dreamer, someone with a sure and steady meter but still throwing off enough sparks to illuminate their vision. Big Surf’s radiance came from Phil Dexter, a petroleum engineer smitten with surfing, but landlocked in the desert. Phil said he was hypnotized when watching surfers. “Waves were very beautiful, especially when people were riding them,” he told one publication. And so he set to work. Against all odds he built the first model of a wave-making machine in his backyard in 1966, and another, larger, full engineering model in an abandoned Phoenix pool hall.

All today’s wave pools started with the same humble roots. Wavegarden dragged a tractor along a pond with their first wave foil. Aaron Trevis of Surf Lakes spent freezing mornings in the Victorian mud testing machinery and models before building the Yeppoon plunger. Pioneer Tom Lochtefeld, could have retired very wealthy after his sale of Flowrider decades ago. But he keeps building, driven by the same mad scientist syndrome as the others. He told us in an upcoming interview, “ I know what the potential is (when designing waves) and I can’t help myself. I know what’s possible and I can’t stop.”

Even the best designs need money to make it all happen. The beach lifestyle has been used to sell everyone from soda to cigarettes. For Dexter, it was a trip to haircare brand Clairol who just so happened to be cashing in on the “surfer look” of the sixties. Today it’s a bit different as investors remain in the shadows until everything pans out. Without big brands investing in a wave pool (although Quiksilver and Ron Jons have tried) today’s crop of funders is pure Wall Street. The only visible entity is Michael Schwab – same family as Charles Schwab – who is investing in the Kelly Slater Wave Company as they expand throughout the world.

Big Surf’s tagline was “The incredible ocean in the desert,” and branded their shoreline Waikiki Beach. It was uninspired, low-fi marketing as there wasn’t any competition at the time. Today, surf parks have to be more sophisticated. The Wave Bristol taps the healing nature of surfing in contrast to the Palm Springs Surf Club’s curated party vibe. Urbnsurf projects an image of hot-meter ripping. Big Surf was alone in the space, so a simple “surfing exhibition” much like Duke brought to the shores of the world, sufficed as marketing. But when the denim seventies faded in the glare of the neon eighties, jet-skis demonstrations replaced surfing in the pool. The world wanted something bigger, louder, faster.

Flash forward a few years to the coming age of wave pools. It will be fascinating to see how each outfit adapts and adjusts to stay visible in this crowded space. The huge variety of wave technology combined with the growing subsets of surfing and culture means we will see creative, innovative incarnations of wave riding. And while Big Surf had to ultimately reinvent itself as a waterpark, surfing is so firmly etched into today’s culture that wave pools won’t have to turn away from their roots.

Main illustration by Tiger Hayes. Thanks to Tempe Magazine sources Rob Denney and John Malpede.

Related Coverage